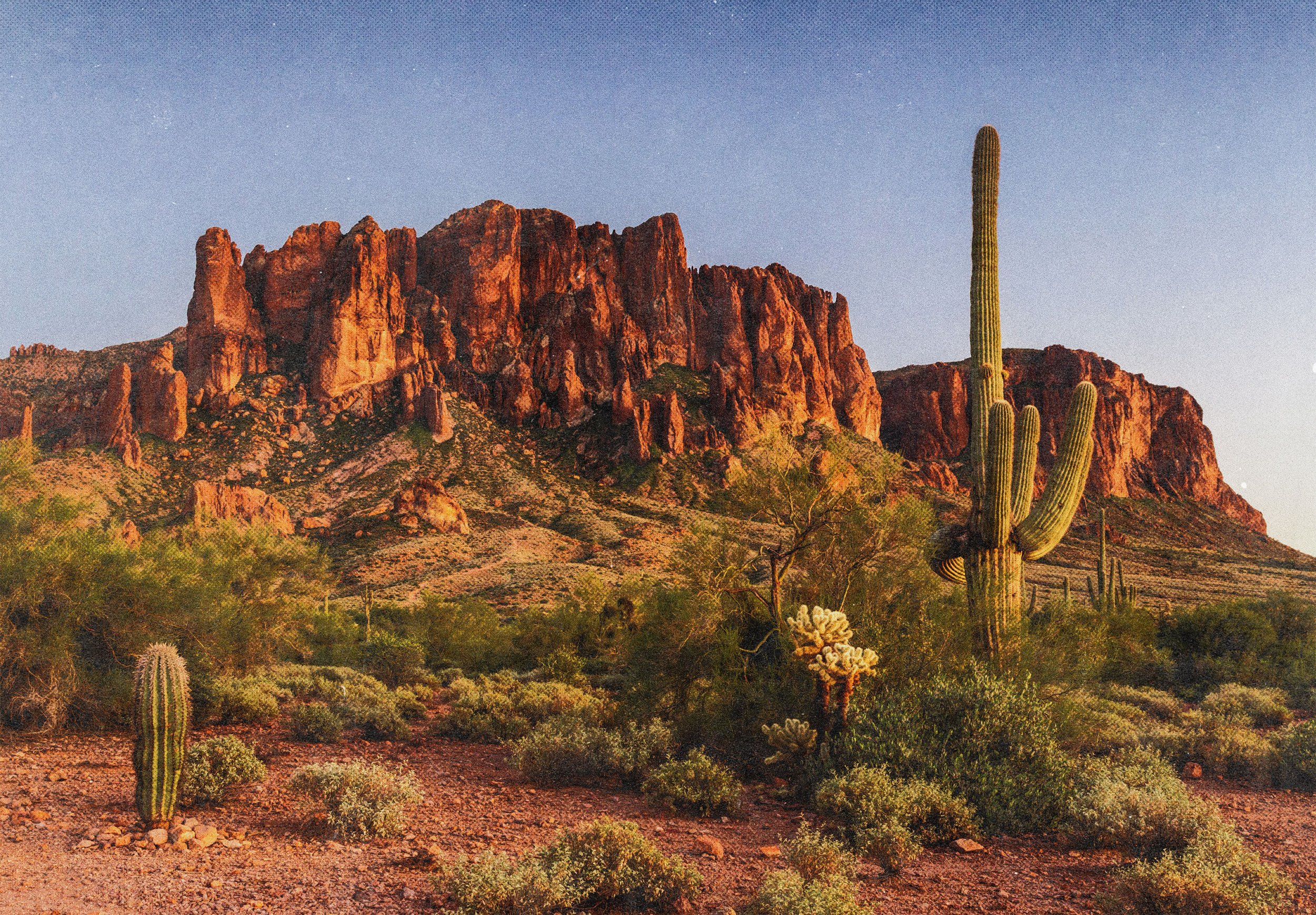

Verde Valley

Desert vibes and Arizona skies.

I. Orientation

I came to Sedona to listen for what wants to be built here.

I was invited into a design research immersion on the land of Verde Valley School, exploring the possible emergence of a new kind of wisdom center. Not a school in the traditional sense, but a place for adult learning shaped by land, experience, and lived practice rather than instruction alone.

Before imagining anything, I needed to spend time on the ground.

The valley works on you slowly. Red rock walls hold the horizon in place. Light moves deliberately, stretching shadows across stone and juniper. The air feels dry and exacting. Sound carries. Silence carries more.

People speak of Sedona in shorthand. Energy. Vortices. Crystals. The town obliges these expectations loudly. Shops and signage promise alignment, healing, awakening.

But beneath that layer is something steadier.

Sedona feels like a place of convergence. People arrive here not to add something new to their lives, but because something old is no longer working. The land doesn’t soothe. It sharpens. Whatever you bring with you comes into clearer relief.

I treated the visit as a practice in restraint. To resist projecting a future onto the place. To notice where attention was being invited and where it was being resisted. To feel the difference between ideas that landed easily and those that slid off the surface.

It became clear quickly that this is not a neutral landscape.

Something here is gathering. Slowly. Patiently.

Brenda, a beloved repurposed school bus on the Verde Valley School campus.

II. What the Field Revealed

Thread One: An Educational Experiment

The campus reveals itself through use.

Hand-built structures are connected by dirt trails worn in by years of walking. A seed library sits near the gardens. Horse stables and an equestrian program edge the land. An operating organic farm supplies produce to the dining hall, with recycled materials everywhere, including an old school bus repurposed as a tool shed. A ceramics studio hums quietly, pottery wheels and kilns in steady rotation.

Students spend more time outside than inside. Moving between places. Working. Carrying tools. Learning with their hands as often as their heads.

Nothing about this place announces itself as a school in the traditional sense. There are no long hallways or rows of lockers. No sense of being managed or contained. The campus feels lived in rather than administered.

This is Verde Valley School.

An open-air pottery studio nestled in the Verde Valley campus.

I wasn’t prepared for how rare it felt. Stepping onto campus carried a strange mix of relief and disbelief, the sensation of encountering a form of human ecology you assumed no longer existed. A place where learning is not abstracted from life, where education still engages the whole person.

Here, students don’t just study ideas. They work. They move. They cook, build, hike, clean, repair. Physical labor is not extracurricular. It is formative. The land is not a backdrop for learning. It is part of the curriculum.

Classes spill outdoors. Biology happens in creeks and canyons. Anthropology shows up in hands-on making. Wilderness trips stretch students past comfort and into responsibility for one another. Learning is inseparable from effort, weather, fatigue, and cooperation.

What struck me most was the posture of the place. There is an assumption here that young people are capable of far more than we usually ask of them. That responsibility is not a burden, but a catalyst. That curiosity deepens when it is tethered to real consequence.

I found myself wishing my sons could experience this kind of education. Not because it is idyllic, but because it is demanding in all the right ways. It asks students to pay attention. To contribute. To understand themselves as part of a larger whole.

VVS feels like an endangered way of being.

Not because it is outdated, but because it refuses the dominant logic of modern education. Speed. Abstraction. Optimization. Instead, it moves at the pace of formation.

Standing there, it became clear that this school is not an anomaly within Sedona. It is a continuation. A modern expression of something this land has always known how to do.

Shape humans through lived experience.

The iconic Gretchen Warren Chapel at Verde Valley School.

Interlude: A Founding Response

Just before World War II, Barbara and Hamilton Warren met by chance at a small posada in the Guatemalan highlands. A brief exchange. A moment of nervous charm. A bouquet of torch ginger flowers left quietly in a room. What lingered was not the romance of the meeting, but a shared curiosity about the world and their place within it.

Years later, shaped by two world wars and the rising tide of cultural misunderstanding, they found themselves returning to a single question:

What can we do to make the world a better place?

Their answer was simple, and radical for its time. Create a school where young people from different cultures would live, work, and learn together. Where education would extend beyond classrooms into daily life. Where students would be asked to judge one another not by background or belief, but by conduct as human beings.

In 1948, they drove west with their two young children, bought land in the remote red rock valleys outside Sedona, and began building from the ground up. They lived in wall tents. Hauled water from a distant creek. Built slowly, with help from local Indigenous workers. The school emerged not as a monument, but as a working experiment.

That experiment became Verde Valley School.

Nearly eight decades later, VVS remains the last boarding school in Arizona. A living expression of a belief that feels newly urgent: that learning rooted in shared responsibility, relationship to land, and lived experience can still shape more capable, humane human beings.

Seen in this light, the school feels less like an invention and more like a response. One that arose from careful listening, at a moment when the world felt fractured.

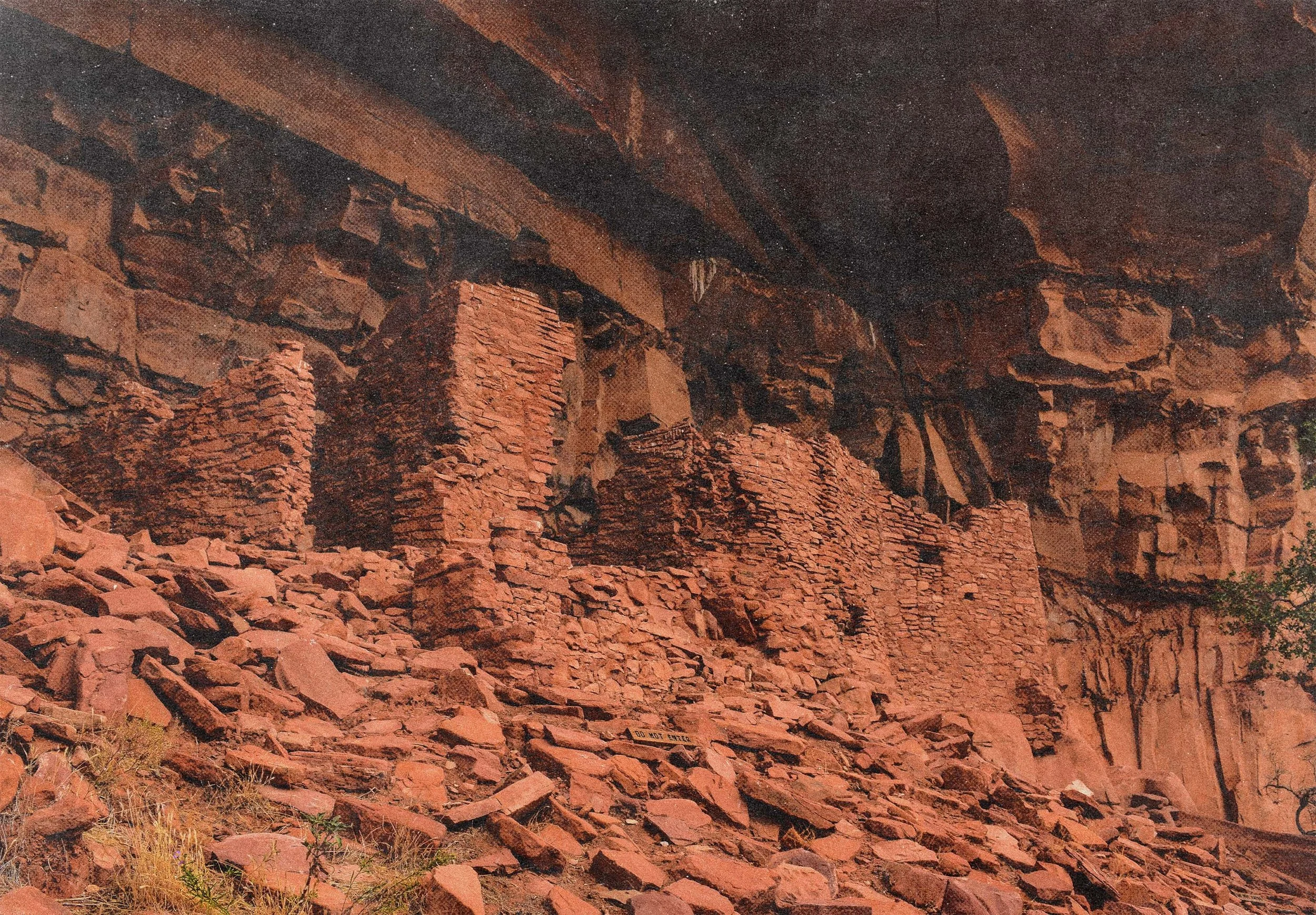

The remarkably preserved Honanki Ruins, a testament to the ancient cultures of the Verde Valley.

Thread Two: An Older Relationship

This land was never empty.

Long before maps, property lines, or the name Sedona, people lived here in sustained relationship with a landscape that demanded attention to survive within it.

The earliest known inhabitants of the region were the Sinagua people. For centuries, they built dwellings into cliff alcoves, farmed along seasonal water flows, and moved in rhythm with weather and terrain. Their name, given much later, means “without water,” a reminder of how carefully life had to be lived here.

They did not vanish. Their presence continued, carried forward through neighboring tribes. For the Hopi Tribe, this region is part of a larger sacred geography shaped through ancestral migrations, where movement itself carried instruction and responsibility. For the Yavapai-Apache Nation, Oak Creek and the surrounding canyons were home, and their people remain present in the region now, maintaining cultural traditions and community life.

What unites Indigenous cosmologies rooted here is orientation.

Land is not scenery. It is alive.

Stories are not metaphors. They are instructions.

Ritual is not a performance. It is maintenance.

Seen through this lens, Sedona’s so-called “energy” reads differently. Less as something to be consumed, more as a call to reciprocity. Certain places ask more of those who enter them. Attention. Restraint. Care.

Indigenous leaders are clear about this. Sedona is not a spiritual theme park. It is a living landscape with obligations.

To be here properly is to enter relationship, not extract insight.

And in that sense, nothing essential has changed. The land has always been teaching this way.

What feels new is only our remembering of it.

Crystals are laid out to soak in the spiritual power of the Sedona landscape.

Thread Three: A Modern Threshold Landscape

Sedona carries a charge that is hard to explain and easy to mislabel.

The surface language is familiar. Vortex maps folded into back pockets. Crystal shops glowing softly in the afternoon heat. Guided meditations at sunrise. Sound baths echoing off canyon walls. Reiki sessions. Chakra alignments. Shamanic journeys. Retreats promising healing, activation, awakening. Meaning, scheduled by the hour.

The town performs this culture openly. It’s easy to dismiss. Easy to mistake the symbols for the substance.

And some people do come here to bypass rather than engage. To collect experiences without consequence. To treat the land as a backdrop for personal mythology.

But stopping there misses the deeper current.

Sedona is one of the few places where inner life is not considered frivolous. Where asking why am I here doesn’t feel indulgent or awkward. Where reflection or repair are legitimate reasons to rearrange a life.

People don’t usually arrive casually. They come when something is already in motion. Careers pause. Relationships loosen. Old identities stop working.

Red rock rises fast and holds the horizon close. Trails lift you from shaded creeks into exposed sky in minutes. The scale resets you. Silence sharpens attention. Whatever you bring with you comes into clearer relief. Whatever you’ve been avoiding becomes harder to ignore.

The land doesn’t promise enlightenment. It offers amplification.

This is why Sedona functions less like a spiritual destination and more like a threshold. A place between chapters.

That’s why people come here.

Not because Sedona gives answers.

But because it makes better questions unavoidable.

The reflection pools near Cathedral Rock at sunset.

III The Pattern Beneath

This place does not resolve through a single lens.

Its essence becomes legible only when multiple systems are held at once:

an educational experiment,

a charged contemporary landscape,

and an ancient, ongoing Indigenous relationship to land.

Beneath the visible differences between a boarding school, a spiritual town, and living tribal presence is a shared orientation. Here, learning happens through encounter. Shortcuts don’t hold. Knowledge arrives through effort, attention, and lived relationship rather than explanation or belief. Whether through wilderness, ritual, physical labor, or shared daily life, Sedona has long shaped humans by placing them inside complexity and asking for response.

What’s striking is not that this pattern exists, but that it keeps reappearing across eras and intentions. When systems here align with the land’s deeper logic, they tend to endure. When they drift toward abstraction or extraction, they feel thin. Temporary. Untethered. The field seems to reward formation over performance, responsibility over ideology.

Over time, several patterns surface again and again.

The land functions as teacher.

Indigenous cosmologies, Sedona’s experiential pull, and Verde Valley School’s pedagogy all treat place as an active source of knowledge rather than a setting. Understanding comes from being with the land long enough for it to shape perception. The place doesn’t just host learning. It conducts it.

Learning here is embodied.

Intelligence is carried through movement, labor, fatigue, weather, and attention. Indigenous practices embed knowledge in ritual and seasonal activity. Sedona invites physical presence and sensory awareness. VVS integrates wilderness and work into daily life. Thinking is inseparable from doing.

The landscape is tuned to thresholds.

This region has long functioned as a place of passage. Indigenous migrations moved through it with purpose. Contemporary seekers arrive during moments of transition. Students at VVS stand at the edge between childhood and adulthood. Stability is rare here. Becoming is constant.

All three resist purely conceptual knowledge.

Meaning emerges through relationship. Knowledge is not something held apart from life, but something formed between people, cultures, land, and self. What matters is how one behaves, not what one claims to believe.

And belonging carries obligation.

Care for land. Care for community. Care for the work required to remain in relationship over time. Participation here is not neutral. The land responds differently depending on what you’re willing to give back.

If a future form of learning were to emerge from this place, these patterns offer quiet guidance. Design with the land as a co-teacher rather than a backdrop. Treat the body as a legitimate instrument of knowing. Honor thresholds as primary moments of formation. Let relationship matter more than content delivery. Tie belonging to responsibility.

The view from Verde Valley School Road.

IV. The Questions That Remain

What kind of learning becomes possible when place is treated as a teacher rather than a setting?

Why do certain landscapes repeatedly become sites of formation across cultures and eras?

What is it about land like this that draws people at moments of becoming?

How do we distinguish between genuine formation and the extraction of insight without responsibility?

Cosmic views and desert dreams: a perfect night for stargazing in Sedona, a certified International Dark Sky Community.

Each Field Note emerges from time spent in a specific place, and from attention paid to the visible and invisible fields that shape what becomes possible there. They are offered not as answers, but as signals.